The Year of the Rat is over, and Chinese cadres smoking in the offices of Zhongnanhai, just West of the Forbidden City, must be relieved they survived. From a Tibetan uprising to the Sichuan earthquake to Olympic debacles and now economic meltdown, the past lunar year left many Chinese feeling ratty.

But before the New Year lanterns have been taken down, the Year of the Ox already has officials seeing red.

This year will see landmark anniversaries with explosive potential. Notably, 10 March marks 50 years since the occupation of Tibet; 4 June will be 20 years since the Beijing Massacre; 20 July will be a decade since the persecution of Falun Gong was launched; 1 October marks 60 years of Chinese Communist Party rule, which may remind many of the estimated 60-80 million who died unnecessarily since ‘liberation’.

Already, anti-government riots are widespread and violent. One extreme case saw a man who had reportedly been beaten by police walk into a Shanghai police station and stab dead six officers in a scene right out of Outlaws of the Marsh. More troubling for Beijing, the murderer received vociferous online support. According to the Telegraph, a message left on the man’s MySpace read: ‘You have done what most people want to do, but do not have enough courage to do’.

What’s more, thousands of factories are shutting down, exports are dropping, and everyone from taxi drivers to teachers seems eager to go on strike. Meanwhile, last year ended with dissidents, progressive intellectuals, and lawyers calling for democratization in an increasingly audacious and unified way.

Easily lost amidst the headlines coming out of China these days is how international dynamics figure in these tensions.

Certainly there are the official, international relations-type dynamics – security issues (North Korea and Iran’s nuclear proliferation), sovereignty issues (over disputed territories like Tibet, Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia), and natural resource issues as Beijing takes its colonialist turn in the South. And of course there is the business level – the ‘future is China mantra’, foreign direct investment projects in coastal cities, and cheap Chinese imports.

But there is also another realm in which various international forces play out – global civil society.

Global civil society

Employed academically since the 1990s, the term global civil society was born of a mother known as civil society and a father called globalization. If civil society is popularly defined as encompassing the space between the state, the market and private family life, then global civil society can be defined as occupying those spaces on a global scale.

In 2001, Helmut Anheier, Marlies Glasius, and Mary Kaldor – three of the scholars who have been spearheading global civil society literature – wrote of the emergence in the 1990s of a ‘supranational sphere of social and political participation in which citizens groups, social movements, and individuals engage in dialogue, debate, confrontation, and negotiation with each other and various government actors’.

In the climate change debate, for instance, besides governments and official multi-national bodies like the United Nations, other actors include international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), activists, scholars, celebrities, and former politicians.

A chronology published in the Global Civil Society Yearbook out of the London School of Economics and compiled by Jill Timms, annually documents a plethora of protests, sit-ins, vigils, and other events that have implications for more than one country – for instance, people in India protesting the execution of Saddam Hussein in Iraq.

Theoretical arguments abound about the appropriateness of global society as a concept, how it should be defined, its extent, and its salubriousness. Yet there is little doubt that some form of global civil society is evolving and that we are all involved in it, whether consciously or not.

And China is at the centre of some of the most fascinating global civil society phenomena today. The past year was one of its most eventful yet, as the battle between an authoritarian regime and its citizens over the definition of the country, its future, and its role in the world stretched far beyond its borders.

Lawyers to the defense

Like in other countries, it has become common for individual activists in China to draw inspiration and support from the international human rights movement. Nowhere is this more obvious than among a rising group of lawyers and activists who call themselves the ‘rights defense’ movement. They are, in many ways, symbolic of what global civil society means for China.

These lawyers – like Gao Zhisheng, Teng Biao, Li Heping, and many others – are versed in United Nations’ conventions and China’s commitments as a signatory. Joining other activists, cyberdissidents, intellectuals, and, most notably, the gamut masses of China’s disgruntled have-nots, they have formed an indigenous movement in pursuit of basic rights, demanding that the ruling Communist Party uphold its promises under China’s constitution and international obligations.

Many have traveled or studied abroad, they maintain regular communication with the Chinese diaspora, and post evidence of abuses and commentary on overseas websites that are then translated into multiple languages. In 2006, they organized a relay hunger strike that saw Chinese throughout the mainland taking turns fasting for a day or two along with fellow protesters in Taipei, New York, London, and Sydney.

The notion of a global civil society, though rarely articulated as such, figures prominently in the consciousness of these grassroots Chinese activists. Their open letters are strewn with calls upon the ‘international community’ (guoji shehui) to stand up to the Party.

When these activists are jailed, and they often are, supporters around the world write letters to Chinese leaders on their behalf.

Sometimes this takes the form of Amnesty International urgent actions – campaigns in which thousands of ordinary citizens across the globe write to a particular government calling for the release of a prisoner of conscience’s release. This early form of global civil society-style activism began in 1961 when British lawyer Peter Berenson issued a call to action in the Observer after reading of two Portuguese students jailed for raising their glasses in a toast to freedom.

Most recently, Professor Liu Xiaobo, a fixture since the days of the 1989 student movement, was arrested, prompting an open letter from his colleagues in the West. Among the signatories were prominent professors who in the past had been loath to take a public stance against Chinese Communist Party abuses.

From the Himalayas down

But in 2008, the Chinese regime’s encounter with global civil society also took a different twist, as abuses in China coinciding with the upcoming Beijing Olympics sparked a much greater international outcry than mere letter writing.

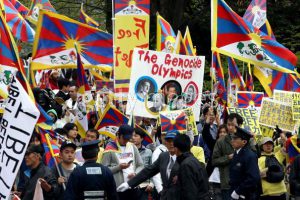

By March, after Tibetan demonstrators were shot dead, protest spread beyond Tibet and surrounding provinces to other countries. From London to Washington to Kathmandu, refugees and other supporters held vigils and sit-ins outside P.R.C. embassies.

Unhappily for Party leaders in Zhongnanhai, these events coincided with the Olympic torch relay. Torchbearers in London were greeted – along with cheering Chinese students waving red flags – by thousands of protesters along the torch route. Not to be outdone, Parisians protesters managed to cause Olympics organizers to extinguish the flame three times.

On the Eiffel Tower and Notre Dame Cathedral, activists hung banners with handcuffs as Olympic rings, and a ‘Free Tibet’ flag decorated San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. As the Games neared, the protests were such a public relations disaster for Beijing that there was even talk of halting the relay altogether.

Meanwhile, alternative relays were already well under way – the Human Rights Torch Relay visited more countries than the official one, each stop accompanied by a press conference, torch bearers, and a rally highlighting rights abuses in China and calling for solidarity with China’s rights defenders.

The result of this global civil society dynamic? At least partially foiling the Communist Party’s effort to pull off a dissent-free, ‘harmonious’ Olympics. For as security forces were going door-to-door inside China detaining bloggers, lawyers, Tibetans, and Falun Gong adherents, the Chinese authorities could not so easily quell the voices of these groups’ international supporters who took up their causes.

‘Genocide Games’

The pre-Olympic backlash to Beijing’s support for the genocidal Khartoum government is an equally important reminder of global civil society’s force.

At the time, the P.R.C. was the major obstacle to a U.N. peacekeeping mission to Darfur. The ‘Not on Our Watch’ campaign featuring Ocean 13’s crew of megastars, international campaigns like the ‘Olympic Dream for Darfur’, and Steven Spielberg’s public statement brought further pressure upon Beijing to respond.

In April, after having previously threatened to veto U.N. Security Council resolutions concerning the conflict, Beijing changed its policy and cleared the way for the U.N. initiative.

As researcher Sabine Selchow of the London School of Economics wrote, ‘There is no doubt the campaign linking China to the genocide in Darfur by naming and framing the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the “Genocide Games”, triggered the change in attitude towards Khartoum’.

Although Darfur’s atrocities continue, although China might still be shipping weapons to Sudan, and although international pressure was insufficient to hold the Party to even a fraction of its human rights promises, the pre-Olympic movement scored a small victory for global civil society. It demonstrated that even seemingly impervious authoritarian regimes are susceptible to international pressures when sufficient will is mobilized.

Going forward in the 21st century – the role of new media

Mobilizations such as those described above are emblematic of a globalised era, not only because of the cross-border messages they convey, but because of the technologies they employ. In a year when the number of Chinese Internet users climbed to the top of the charts, surpassing even the United States, it was only fitting for the full range of new media to play a prominent role in the global civil society dynamics.

The year began with the revival of an old new activist tool – text messaging. In China, where email and phone communications are tightly monitored, text messaging has proven to be a comparatively safe and cheap way of rapidly spreading information.

For over a decade, Chinese have regularly used messaging to organize protests. But last year, text messaging was put to use in a new way – to disseminate missives urging fellow Chinese to renounce their membership in any Communist Party organization.

The movement, known simply as ‘Quit the Party’ (tui-dang) is a unique product of diaspora resources and mainland gusto. It began with the overseas publication of the Nine Commentaries, a compilation of editorials printed by the New York-based Epoch Times critical of the ruling party’s damage to Chinese people and their culture.

The Nine Commentaries’ arguments resonated with millions of Chinese, and soon a movement began of public renunciations of Party membership – statements posted online, street bulletin boards, or through phone calls made to special overseas centers that keep records of the resignations.

Exemplifying the role that new technologies have played in the transnational movement was a December statement made by prominent rights attorney Zheng Enchong in Shanghai, sent by video recording to a forum held in New York.

‘I am very grateful to be able to communicate with friends in Flushing’, said Zheng. ‘Like many mainlanders, I renounced membership in the Communist Youth League and Young Pioneers this year (2008) with my real name’.

This role of new media in global civil society was also central to the pre-Olympic movement. Calls for a boycott – supported by entertainment celebrities, athletes, and watchdog groups like Reporters without Borders – were promoted through cyberspace’s social networks such as MySpace, YouTube and Facebook.

Meanwhile, overseas alternative Chinese media, like New Tang Dynasty Television, last year played a key role in exposing Party corruption in the construction of schools that collapsed during the tragic Sichuan earthquake and aired footage of Tibetan protests from the depths of Gansu province. These further fuelled international attention to the issues. Even more importantly, from Beijing’s perspective, they threatened to influence domestic public opinion through their websites or broadcasts into China.

Two-way street

The Communist Party is very much aware of global civil society’s power to subvert its official discourse or even ferment oppositional challenges. Indeed, according to Chen Yonglin, a former diplomat who defected to Australia, P.R.C. consulates and embassies today are obsessed with countering overseas activities of ‘the five poisons’.

Not to be confused with ‘the five poisonous creatures’ (viper, scorpion, lizard, centipede, and toad), or ‘the five evils’ (tax evasion, bribery, corruption, theft of state property, and stealing economic secrets) – which go by the same Chinese name of wu du – these fabulous five refer to pro-Tibet, Xinjiang, and Taiwan independence groups, the Falun Gong, and democracy activists.

Each of these groups has strong links connecting activists in the P.R.C, Taiwan, and communities in the Chinese diaspora and beyond.

Not a passive actor, Beijing is countering global civil society movements with both soft and not-so-soft power tactics.

Within China, the authorities regularly sentence internationally renowned activists to prison terms on vague charges like ‘inciting subversion’ or ‘leaking state secrets’. The state’s Great Firewall blocks access for Chinese to a wide range of sensitive terms – indeed, a study conducted by the Berkman Center of Harvard found that the Nine Commentaries was one of the most tightly filtered.

Other efforts include monitoring e-mail and mobile phone usage of overseas dissidents, spreading viruses on their listservs, and harassing their family members back in China; training tens of thousands of ‘50 cent Party’ commentators to post party-line remarks online; establishing a state-run global satellite news network and pressuring Eutelsat to stop broadcasting New Tang Dynasty Television to Asia.

Looking ahead

This new Chinese year is expected to see its share of movements and struggles, many of which will again carry international implications to the point that the lines distinguishing domestic and foreign are blurred.

In an evolving global civil society, we are each called upon to choose sides. So while there are scholars who sign letters, there are professors who self-censor their China writings. Where there are American companies like Dynaweb helping Chinese netizens escape web filters through proxy servers, there are also American companies like Cisco arming the Chinese Public Security Bureau with advanced Internet-monitoring technology, as Ethan Gutmann has documented in Losing the New China.

A decision to sign a petition or join a protest, as well as a choice to be a passive bystander, effects not only the lives of millions of Chinese, but shapes the kind of global civil society we live in. For if there is anything that the Chinese example shows us, it is precisely that the struggles of people in faraway lands are no longer only theirs. They are global.

If a mother in Kansas City, Manchester, or Brisbane can unknowingly poison her baby with an imported tainted milk product, so can her activism help a Chinese cyber dissident escape torture. When joined by others from around the world who share similar ethics, she has the power to stop the world’s strongest authoritarian government.

Leeshai Lemish writes about human rights, activism, and the role of media with a focus on China. He contributes to the Global Civil Society Yearbook’s chronology and wishes to thank unnamed colleagues in China for their first-hand information.