China has been on a high growth path for more than 30 years. It’s unlikely that a country of this size can continue to grow at this pace

for another 20 years. Many economies in the world have experienced high growth periods. Within the period of high growth, they successfully transitioned from an under developed economy into a truly market economy. Unlike these economies, after 30 years, it is apparent that China’s export oriented strategy actually harms the economic structure.

The world is in a mess.

The year 2009 could be an ugly year. The World Bank and other major institutions predict that it will be the first year of global gross domestic product decline since World War II, and the first trade decline in 80 years.

The United States, triggered by its domestic subprime mortgage crisis, has dragged the world into the Great Recession, a new term to compare the severity of the current turmoil with the Great Depression in the 1930’s. In March, the CEO of Blackstone Group LP, a private equity company, said that up to 45% of the world’s wealth has been destroyed.

Looking forward, not only are the developed countries such as the U.S., Europe, and Japan experiencing the sharpest contraction in the post-war period, by a significant margin, but emerging and developing economies, as well as in low-income economies, will continue to be impeded by financial constraints, low commodity prices, and weak demand.

BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China), once touted by many as the new engine of the world economy, is now left with I and C only, as Russia and Brazil are losing power. China, standing out with a $2.0 trillion foreign exchange reserve together with a gigantic 4.0 trillion yuan stimulus package, is warmly expected to lead the world out of recession.

Those expectations are driven by justified motives. The U.S. hopes China will buy more Treasury bonds so that the Federal Reserve can print fewer inflationary dollars; the IMF wants more contributions from Beijing so as to rescue collapsing economies like Iceland, Estonia, and Latvia; and France wishes to sell China more Airbus jets.

Once a world factory and global seller, China is now winked at to become a generous buyer.

But can China meet such expectations?

Troubles at Home

On March 5, Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, in his annual report to the National People’s Congress in Beijing, warned that the global financial crisis poses “unprecedented difficulties and challenges” to the nation, and insisted that the economy would strive to maintain a “fast and steady” 8 percent growth rate in 2009.

A week later, the World Bank slashed China’s 2009 economic growth forecast to 6.5 percent, a very rosy number for many countries, but alarming for China.

For political reasons, Beijing feels it necessary to maintain a high growth rate, despite the many criticisms of its blind pursuit of a high gross domestic product (GDP). In the past decade, the nation has been growing with an average annual double digit GDP rate and an ever increasing scale of social unrests at the same time.

According to government sources, in 2005, there were 70,000 emergent large scale incidents of social unrest across the country; in 2007, the number climbed to over 80,000, a rate of one uprising every six minutes. [1] In senior communist officials’ thinking, the nation needs a GDP growth rate of 8 percent as a threshold to keep enough people at work and avoid social upheaval.

Although Prime Minister Wen expressed a strong confidence verbally, the reality is worrisome:

• Overall economic growth slowed to 6.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008 from 2007’s stunning 13 percent rate as exports plunged and domestic sales of real estate, autos and other goods declined; [2]

• As many as 15,000 factories in the Pearl River Delta are estimated to have closed due the decrease in demand, causing the loss of millions of jobs; [3]

• The Government reported that industrial profits dropped 37 percent in the first two months of 2009; [4]

• Exports were down 25.7 percent in February year-on-year, while imports had meanwhile dropped 24.1 percent; [5]

Beneath the gloomy figures lies an ailing industrial structure, formed and reinforced by an export oriented development strategy. In 2005, Commerce Minister Bo Xilai dazzled the nation and exemplified the strategy with the statement, “China has to sell 800 million shirts in order to buy one Airbus airplane.”

Following this policy, the economy has boomed. From 1978 to 2007, China’s total foreign trade (exports and imports) has grown from $20.64 billion to $2.17 trillion, more than 100 fold within three decades. Its proportion of GDP also grew from 9.74% to 67%. The trade surplus grew from $24.1 billion in 2000 to $262.2 billion in 2007.

Along with the increase in numbers came a thirty-year transition in which China changed from a nation sealed off from the outside world to one that is overly reliant on it. To a large extent, the nation’s economy is now driven by consumers thousands of miles across the ocean.

An export oriented model built upon cheap labor and massive consumption of raw materials directly exposes the economy to external fluctuations. Not only is the fall of international demand delivering an immediate blow, but the huge foreign exchange reserve accumulated from years of trade surplus is highly vulnerable to the ups and downs of the dollar. At the same time, over investment and over production is dragging the nation into a quagmire.

Inadequate Domestic Demand

What about getting Chinese to buy?

Remember, one necessary element of the export oriented development strategy is cheap labor. If labor is not cheap enough, China’s exports cannot compete on the international market. But, there is another side of the coin. Even though GDP figures are high, the incomes of the Chinese people, those cheap laborers, are quite low.

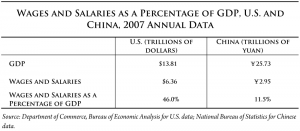

The table below calculates and compares income as a percent of GDP for the U.S. and China, using 2007 annual data. As we can see, in the U.S., income is about 46.0% of the economy, while in China the percentage is only 11.5%. The ultimate goal of developing the economy is to improve living standards, or the income level. Wages and salaries are the major source of income for an average family. In the U.S., this figure is almost half of the nation’s gross domestic product. Government spending and private investment accounts for the remainder. In China, the fact that the figure is only a little above one tenth demonstrates that, although China’s GDP growth has been high, people’s income is not growing as it should.

If China continues to depend on selling labor intensive goods, it will be quite difficult to raise the nation’s income level. Unfortunately, there is no sign of discontinuing this strategy. Since the second half of 2008, the government has increased the export subsidy six times, with the most recent one starting on April 1. [6]

Not only is the Chinese people’s income proportionately low; it is not distributed evenly. Many studies have confirmed the widening income gap between the urban and rural populations. Economic theory postulates that, with a fixed total amount of wealth, the more unequal its distribution is, the lower the total consumption level it will achieve.

The income inequality is to a large extent attributable to the political system. Without the rule of law to guarantee a market place of fair competition, the poor find it extremely difficult to improve their social and economic status.

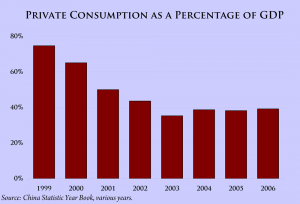

That’s why private consumption in the U.S. accounts for almost 70% of GDP, while in recent years in China, it accounts for less 40%.

The government also understands that the key to restoring growth is to get Chinese people to buy, but it’s not an easy task. Without a social security system in place, people just don’t have confidence in the future. They would rather save than spend, especially during the current economic turmoil.

More importantly, the government itself is making it hard for people to buy.

The Grabbing Hand

One example is the housing market.

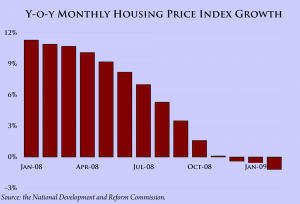

Housing, once the most profitable sector, is now experiencing difficulties. Ever since December 2008, the average housing price in more than 70 cities has been declining.

As the housing sector is affecting other segments of the economy, the government has taken a variety of measures in an attempt to boost the market, including removing various housing taxes; adjusting the mortgage rates; and lowering the down payment ratio. [8]

However, the market is hardly moving, as the price is just too high for the average family.

A recent Xinhua article revealed that Beijing’s housing price ratio is 23 to 1. The average housing price is 23 times the income of an ordinary urban residential family. The World Bank standard is 5 to 1. By any standard, the price is outrageously high. There is simply no way for an average family to afford the mortgage payment. In Beijing, more than 30% of residential housing is standing empty. [7]

During the National Political Consultative Conference held in March, after investigating the cost of real estate development in 9 cities, the All-China General Chamber of Industry & Commerce, a government affiliated association, published a report, “Why Are China’s Housing Prices So High?” The report revealed that as much as 49.42% of the development costs, including land use fees and taxes, goes to the government. [9]

The ratio of development costs in Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou were 64.5%, 48.28%, and 46.94% respectively.

Not counting land use fees, the taxes paid by developers are 26.06% of the total cost and 14.21% of the total revenue.

The report disclosed that out of the total sales revenues, 37.36% goes to the government while 26.14% goes to the developer. If other non-tax fees levied by various agencies are counted, the government’s share of the pie exceeds 40%.

The report concludes that the government is the largest beneficiary of the housing market. As the government’s portion of the housing price, usually inelastic, is a big source of fiscal revenue for local governments, there is little room to lower the price.

If the government can give up a portion of its claim to the pie so that the housing price can be lowered to an affordable level, the demand will balloon and the economy will grow. In return, unemployment will decline and the communist rulers in Beijing may stay a little longer. However disastrous it is at the national level, in a system without the rule of law or checks and balances, grabbing as much and as fast as possible is the prevailing rationale at the individual level.

Old Wine in a New Bottle

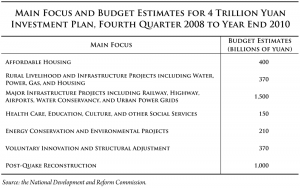

On the home page of the National Development and Reform Commission, there is a table explaining where the 4 trillion yuan stimulus package goes.

There is nothing new.

Over the past three decades, the Chinese economy has basically been driven and characterized by projects of cement and steel. When many foreigners visit China, they are dazzled by the high-rises and new buildings. However, this is quite often their impression of China’s “economic miracle,” and nothing more. If the current stimulus package is 4 trillion yuan, the Chinese economy has been “stimulated” in this same fashion for decades. Clearly this is not the solution to the current crisis.

China’s economic crisis has its own origin. Fundamentally, the crisis is caused by a quantity driven, unbalanced, and unsustainable growth model. With the current political system, where a few people at the top decide who will lose and who will gain, the outcome is bound to benefit a small group at the cost of the people and the nation as a whole.

The global financial crisis does not hurt China’s banking system that much because it’s too young to play those highly risk games. The big hit comes from exports. Thus the government has to substitute its spending in place of foreigners, knowing that boosting domestic demand is very difficult.

Now the problem is that there is not enough demand to absorb the over production. The added stimulus investment, mostly more cement and steel projects, does nothing to help, but only exacerbates the imbalance.

With the call from the central government, state and local governments also matched 14 trillion yuan in “stimulus” money. Local officials have incentives to do so as the GDP figure is one of the few measures of the official’s performance. It matters little whether the figure comes from over investment, inventory or products consumed by the people.

Some economists have boldly suggested that the government just distribute the stimulus money to people so that they can spend. However, as of now, there is no sign of implementing this advice on a large scale.

If domestic problems are not troubling enough, the value of its foreign exchange reserves is another headache. Over the years, China has tried to profit from investing in the U.S. market, but without much success. Recently, the central banker Zhou Xiaochuan’s call for adopting an international currency to replace the U.S. dollar reflects China’s anxieties, but Hu Jintao did not mention the idea when he met with U.S. President Obama.

Anyway, China’s economic power is still not a direct challenge to the U.S. What it can do now is to quietly purchase energy products and raw materials while the prices remain low.

Conclusion

China has been on a high growth path for more than 30 years. It’s unlikely that a country of this size can continue to grow at this pace for another 20 years. Many economies in the world have experienced high growth periods. Within the period of high growth, they successfully transitioned from an under developed economy into a truly market economy. Unlike these economies, after 30 years, it is apparent that China’s export oriented strategy actually harms the economic structure.

The pain of the current financial crisis is felt globally. While every world government is probing for new strategies, it seems none has emerged with a clear and effective vision.

This juncture actually provides China with an opportunity to adjust and establish a new path that focuses on the quality instead of quantity of the economy. However, this cannot be achieved without a change in the social system and a transition into a truly market economy. Whether the power elite can rectify the current, deeply ingrained mechanisms of economic interaction remains to be seen.

Footnotes:

[1] Nanfang Daily, March 19, 2009http://opinion.nfdaily.cn/content/2009-03/09/content_4971421.htm

[2] The Associated Press, March 26, 2009

http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5j1FZRNA_nf7XY7YePH-Od-tdunFAD9766JN80

[3] Reuters, March 9, 2009

http://www.reuters.com/article/reutersEdge/idUSHKG8557120080309?pageNumber=1&virtualBrandChannel=0

[4] National Bureau of Statistics

http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjfx/jdfx/t20090327_402548124.htm

[5] AFP, March 10, 2009

http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5jh2-AF2oie2g3bgxl9vxJFtmLQqA

[6] State Administration of Taxation’s website

http://www.chinatax.gov.cn/n8136506/n8136548/n8136623/8917340.html

[7] Xinhua, April 3, 2009

http://news.xinhuanet.com/house/2009-04/03/content_11123014.htm

[8] Outlook Weekly, a weekly magazine under Xinhua News Agency

http://news.sohu.com/20081027/n260262625.shtml

[9] The Beijing News, March 6, 2009

http://news.thebeijingnews.com/1142/2009/03-06/008@025301.htm